As a historian of religion, I know the power of relics. The term comes from the Latin reliquiae (“remains”), meaning the body or personal effects of a revered person.

Last week, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) repatriated the remains—a single tooth—of the slain Congolese independence leader Patrice Lumumba (1925-1961). That only a tooth survives is a metaphor for the brutality of colonialism and its neocolonial aftermath in the DRC’s history.

From 1877 to 1908, when the country was known as Congo Free State and ruled as the personal possession of King Leopold II of Belgium, its people endured unspeakable violence at the hands of the Force Publique, the military that enforced production quotas in the rubber industry. Workers who failed to collect the required amount of sap from the rubber vines were punished by having hands or limbs amputated—a story told in King Leopold’s Ghost (1998) by Adam Hochschild.

As my IUPUI colleague Didier Gondola has recounted in his history of Congo, among the first outsiders to witness the atrocities were two African-American missionaries: George Washington Williams, a Baptist minister and U.S. Civil War veteran, and William Henry Sheppard, a Presbyterian minister. Their protests were a prelude to the international campaign that led Leopold to cede control of the country to the Belgium government in 1908.

Missionaries continued to arrive during the period of the Belgian Congo (1908-1960). One of them was my great-aunt Marie Ropp, whose story I’ll tell in an upcoming blog post. She died in 1911 in Elisabethville (now Lubumbashi).

A half century later, the 34-year-old Patrice Lumumba, charismatic leader of the Congolese National Movement, became the first prime minister of the newly independent nation.

The triumph of independence was short-lived. As American historian Bruce Kuklick and Belgian historian Emmanuel Gerard have written, Congo’s own politicians were competitors in a struggle involving “a righteous but flawed United Nations; an arrogant and destructive United States; and an entrenched Belgian bureaucracy determined to maintain imperial prerogatives.”

Kuklick and Gerard note that no high-ranking officials in the United States had much knowledge of Congo. That didn’t stop the CIA from seeking to assassinate Lumumba on the pretext that he was a pawn of the Soviet Union. Though the CIA plan failed, the U.S. government got its wish when Lumumba’s Congolese and Belgian opponents conspired against him. Following a coup by Colonel Joseph Mobutu, Lumumba was arrested and fell into the hands of secessionists in Katanga province. Taken to a house on the outskirts of Elisabethville, he was tortured and executed by Katanga soldiers under the command of two Belgian police officers.

Later, in bungled attempts to hide the evidence, Lumumba’s body was buried and reburied before being exhumed again, dismembered, and dissolved in acid. A Belgian officer, Gerard Soete, saved a tooth as a trophy, which a Belgian judge in 2020 ordered returned to Lumumba’s family.

On June 20, 2022, Lumumba’s children received the tooth, contained in a flag-draped coffin, at a ceremony in Brussels. They accompanied the remains back to the DRC for interment in a mausoleum in Kinshasa. “His spirit, which was imprisoned in Belgium, comes back here,” his nephew, Onalua Maurice Tasombo Omatuku, told Agence France-Presse.

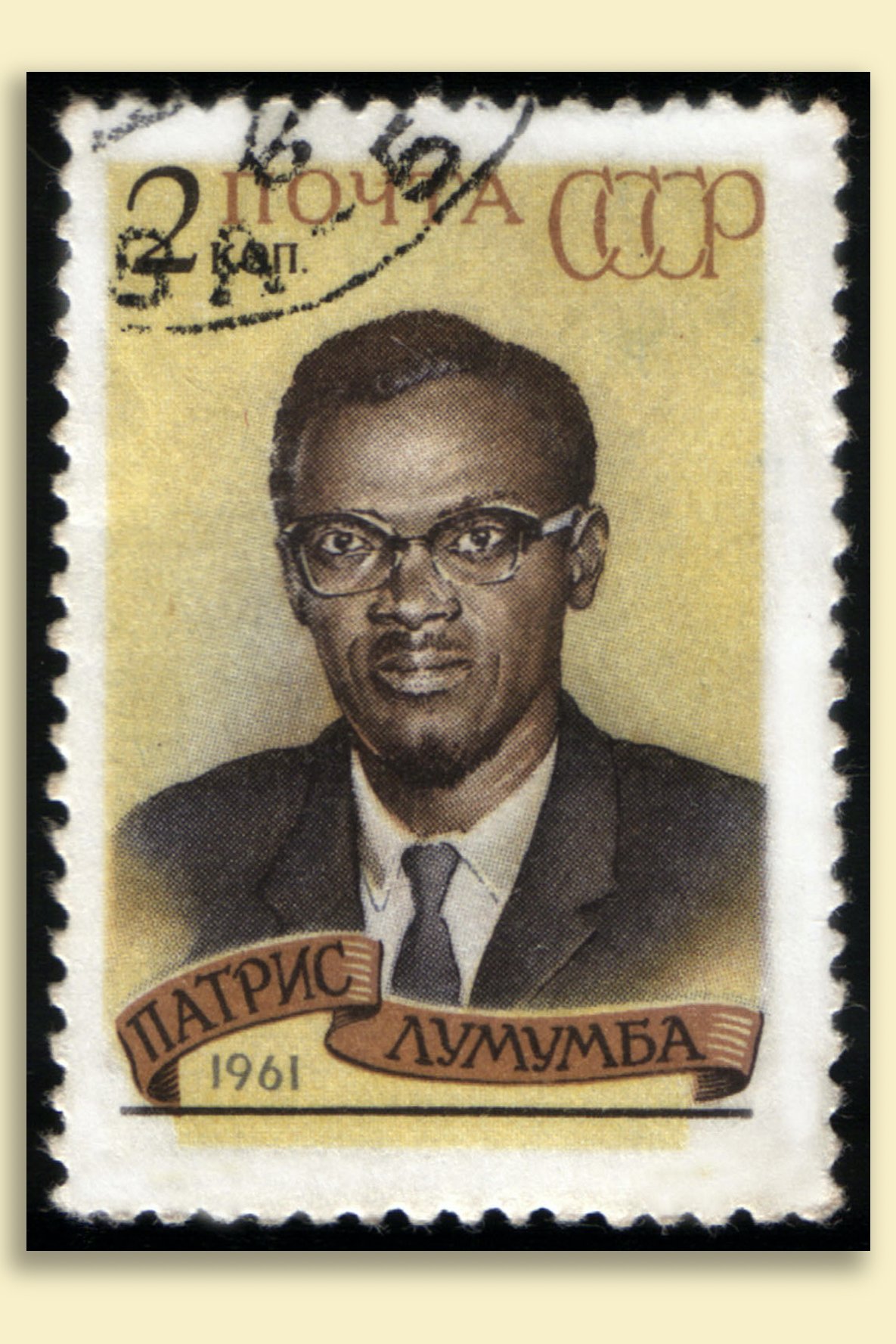

Lumumba’s spirit had already grown larger than life as a symbol of revolutionary resistance. Soon after his death became public in February 1961, protests erupted around the world. Some countries, including the U.S.S.R., issued postage stamps honoring him. Malcolm X called him “the greatest black man who ever walked the African continent.” Cities renamed streets in his memory.

One such street I know personally is Lumumbastraße in Leipzig, Germany, so named during the Communist regime of the German Democratic Republic. A bust of Lumumba was erected there in 1961 at the Herder-Institut of Karl Marx University, where many foreigners have studied the German language. After the fall of the Berlin Wall, when Karl Marx University reverted to its original name of Leipzig University, the bust was damaged and ultimately removed. But in 2011, a replica of the original was installed to mark the 50th anniversary of Lumumba’s death.

I saw the original bust when I studied at the Herder-Institut in 1993. At that time, a recently reunified Germany was still coming to terms with East Germany’s Communist history, in which Lumumba symbolized resistance to the West.

In the United States, anti-Communism for decades prevented a similar celebration of Lumumba’s legacy. Within weeks of his death, for example, an editorial in the evangelical Protestant magazine Christianity Today accused Moscow of orchestrating the worldwide protests of his murder. Lumumba’s demise, the editors wrote, was “a sharp blow to Soviet aspirations in the Congo.”

Though Lumumba had been elected democratically, the United States government backed the authoritarian one-party regime of Mobutu, who renamed the country Zaire in 1971. When Mobutu was overthrown in 1997, the country took its present name of the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Today, the DRC is writing a new chapter in memorialization and civil religion as Lumumba’s remains receive the honor they were so long denied.

© 2022 by Peter J. Thuesen. All rights reserved

Bibliographical Note

Adam Hochschild, King Leopold’s Ghost: A Story of Greed, Terror, and Heroism in Colonial Africa (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 1998). Ch. Didier Gondola, The History of Congo (Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 2002), 72-73. Emmanuel Gerard and Bruce Kuklick, Death in the Congo: Murdering Patrice Lumumba (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2015), 3, 148, 207-8. Ludo de Witte, The Assassination of Lumumba, trans. Ann Wright and Renée Fenby (London: Verso, 2001), 127-28, 140-43. Jason Burke, “Belgium Must Return Tooth of Murdered Congolese Leader, Judge Rules,” The Guardian, September 10, 2020. “Remains of Independence Hero Lumumba Arrive Home,” Agence France-Presse, June 22, 2022. Malcolm X, By Any Means Necessary, 2nd ed. (New York: Pathfinder, 1992), 92. Eric Singh, “Leipzig Honours Lumumba,” African Information Centre, May 17, 2011. “‘Push Button’ Riots Now Promote Communist Goals,” Christianity Today, March 13, 1961, pp. 25-26.

Illustration Credits: Wikimedia Commons