In spring 1993, I was a senior at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill nervously awaiting word from the Ph.D. programs to which I had applied. I still remember the thrill of receiving an acceptance letter from Princeton University signed by Albert Raboteau, dean of the graduate school.

Albert Raboteau was a familiar name. As a religious studies major, I had encountered his classic Slave Religion (1978), a pioneering study of the rise of a distinctive Christianity among enslaved peoples in America.

He was a professor in what would become, after I accepted Princeton’s offer, my new academic home: the Department of Religion, which has been well represented among Princeton’s graduate school deans. (My own dissertation adviser, John F. Wilson, was dean of the graduate school from 1994 to 2002.)

As a new graduate student, I was more than a little intimated to serve as a teaching assistant in Professor Raboteau’s class on African-American religious history. But I soon discovered that Al (as graduate students knew him) was warmhearted, soft-spoken, and unpretentious.

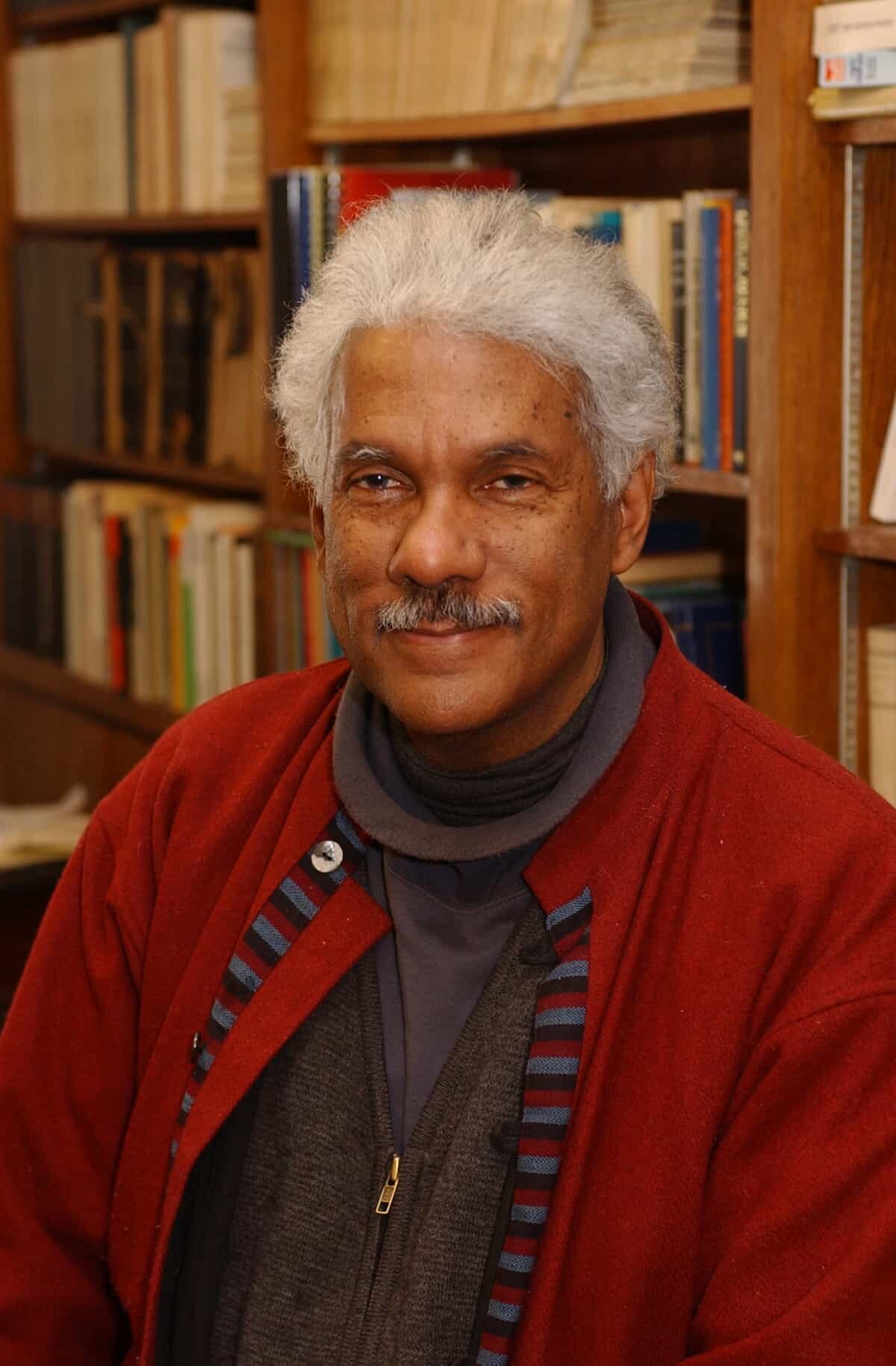

Albert Raboteau died last weekend, September 18, at age 78. Princeton University and Americanist historians everywhere have lost a renowned scholar, a trusted friend, and a gracious human being.

Nearly three decades after I began graduate school, I’m still teaching Professor Raboteau’s work. This week in my American Religion class at IUPUI, my students are reading his essay, “Richard Allen and the African Church Movement,” collected in A Fire in the Bones: Reflections on African-American Religious History (1995).

My appreciation for Al’s lyrically written scholarship has only increased over the years. But my favorite memory of him is not about words but images. While I was in graduate school, I was intrigued to learn that Al was enrolled in a class on icon painting (or as Eastern Orthodox Christians call it, icon “writing”). A convert to Orthodoxy to from Catholicism, Al had embraced that most characteristically Eastern Christian form of piety—meditation on images.

I’ve since come to realize how fitting this was. A scholar who had written about the biblical images that animated the Black Church was now creating literal images of Christ and the saints. He later wrote about the experience of seeing a Russian Theotokos (Mother of God) icon in an exhibit at the Princeton Art Museum and how this had turned him on the path to Orthodoxy. “She seemed to hold all the hurt in the world with those eyes,” he recalled. “I stood in front of her for a long time. I gazed at her and she gazed at me.”

Images have an unaccountable power. Though I’ve spent much of my career writing about controversies over doctrine, I’m convinced that images hold greater sway over the psyche than any rational argument. This is no less true of the verbal images—the biblical stories—that enliven the Black Church. One of Professor Raboteau’s most famous essays, “African-Americans, Exodus, and the American Israel,” is about the power of the Exodus motif in the African-American experience.

To a greater or lesser degree, all Christians dwell in the Bible’s images. The hold of biblical imagery over the Christian imagination is vividly expressed in James Baldwin’s Go Tell It on the Mountain (1953), which Al Raboteau assigned to his class when I was his TA. As Deborah, one of the novel’s characters, tells her husband, Gabriel (a pastor): “ain’t no shelter against the Word of God, is there, Reverend? You is just got to be in it, that’s all.” To be “in it” means to make the Bible’s characters one’s own, to inhabit biblical stories as if entering a life-size mural of salvation history.

Some Christians, especially the Orthodox, also dwell in literal images, filling their churches and homes with icons. The Orthodox justification for the use of icons is twofold: humans are created in the image of God (Genesis 1:27), and God becomes incarnate in Christ. Humans, like Christ himself, are images of the invisible God.

When I imagine Al Raboteau in the afterlife, I picture him writing an icon. May we follow his example and learn to find the divine image in each other.

© 2021 by Peter J. Thuesen. All rights reserved

Bibliographical Note

Albert Raboteau described his encounter with the Russian icon in Albert J. Raboteau, A Sorrowful Joy (2002; Reprint, Eugene, Ore.: Wipf and Stock, 2012), 41-42. His essay “African-Americans, Exodus, and the American Israel” appears in A Fire in the Bones (cited above).